Using async await in Swift to build an image loader

Async/await will be the defacto way of doing asynchronous programming on iOS 15 and above. I've already written quite a bit about the new Swift Concurrency features, and there's still plenty to write about. In this post, I'm going to take a look at building an asynchronous image loader that has support for caching.

SwiftUI on iOS 15 already has a component that allows us to load images from the network but it doesn't support caching (other than what’s already offered by URLSession), and it only works with a URL rather than also accepting a URLRequest. The component will be fine for most of our use cases, but as an exercise, I'd like to explore what it takes to implement such a component ourselves. More specifically I’d like to explore what it’s like to build an image loader with Swift Concurrency.

We'll start by building the image loader object itself. After that, I'll show how you can build a simple SwiftUI view that uses the image loader to load images from the network (or a local cache if possible). We'll make it so that the loader work with both URL and URLRequest to allow for maximum configurability.

Note that the point of this post is not to show you a perfect image caching solution. The point is to demonstrate how you'd build an ImageLoader object that will check whether an image is available locally and only uses the network if the requested image isn't available locally.

Designing the image loader API

The public API for our image loader will be pretty simple. It'll be just two methods:

public func fetch(_ url: URL) async throws -> UIImagepublic func fetch(_ urlRequest: URLRequest) async throws -> UIImage

The image loader will keep track of in-flight requests and already loaded images. It'll reuse the image or the task that's loading the image whenever possible. For this reason, we'll want to make the image loader an actor. If you're not familiar with actors, take a look at this post I published to brush up on Swift Concurrency's actors.

While the public API is relatively simple, tracking in-progress fetches and loading images from disk when possible will require a little bit more effort.

Defining the ImageLoader actor

We'll work our way towards a fully featured loader one step at a time. Let's start by defining the skeleton for the ImageLoader actor and take it from there.

actor ImageLoader {

private var images: [URLRequest: LoaderStatus] = [:]

public func fetch(_ url: URL) async throws -> UIImage {

let request = URLRequest(url: url)

return try await fetch(request)

}

public func fetch(_ urlRequest: URLRequest) async throws -> UIImage {

// fetch image by URLRequest

}

private enum LoaderStatus {

case inProgress(Task<UIImage, Error>)

case fetched(UIImage)

}

}In this code snippet I actually did a little bit more than just define a skeleton. For example, I've defined a private enum LoaderStatus. This enum will be used to keep track of which images we're loading from the network, and which images are available immediately from memory. I also went ahead and implemented the fetch(:) method that takes a URL. To keep things simple, it just constructs a URLRequest with no additional configuration and calls the overload for fetch(_:) that takes a URLRequest.

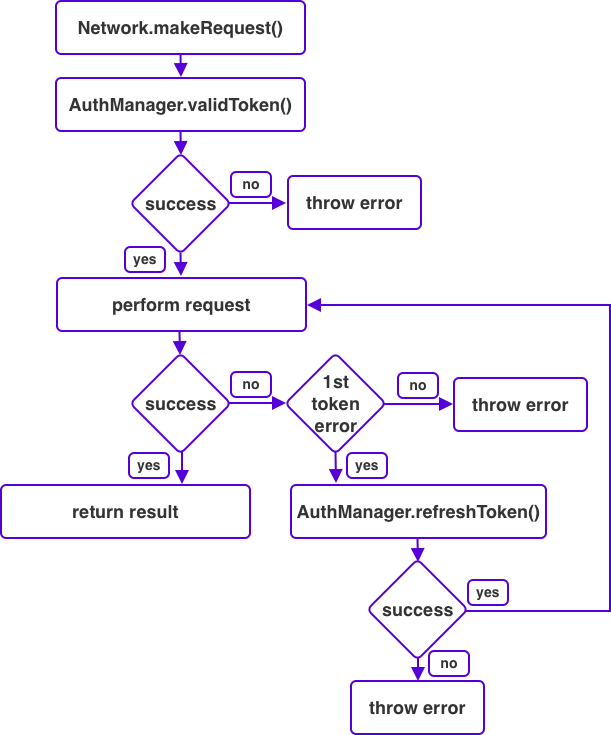

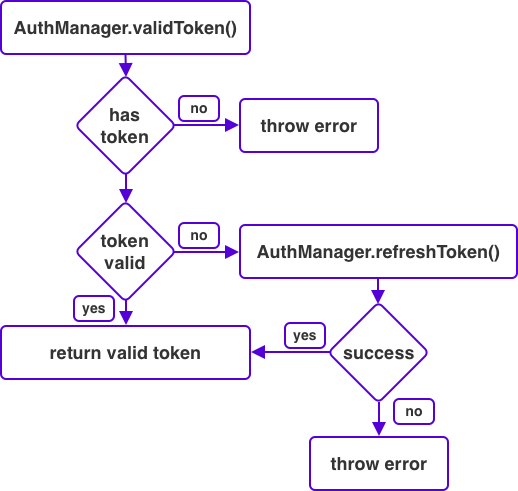

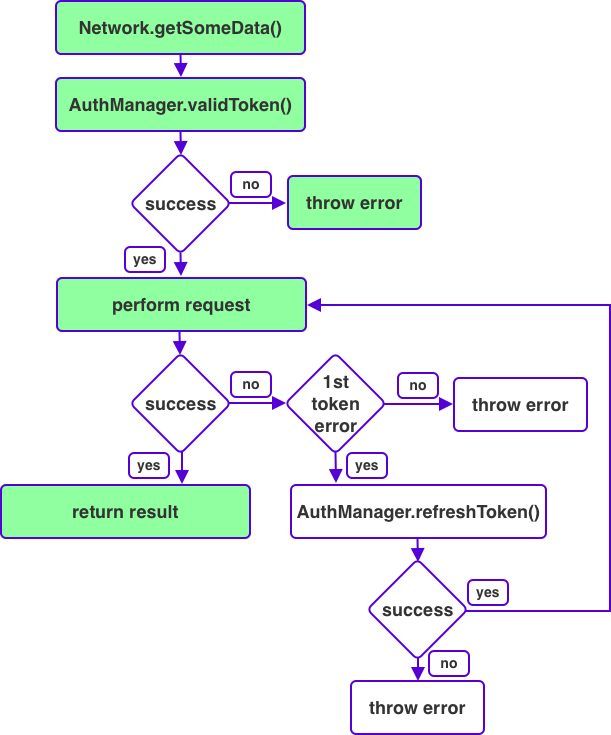

Now that we have a skeleton ready to go, we can start implementing the fetch(_:) method. There are essentially three different scenarios that we can run into. Interestingly enough, these three scenarios are quite similar to what I wrote in an earlier Swift Concurrency related post that covered refreshing authentication tokens.

The scenarios can be roughly defined as follows:

fetch(_:)has already been called for thisURLRequestso will either return a task or the loaded image.- We can load the image from disk and store it in-memory

- We need to load the image from the network and store it in-memory and on disk

I'll show you the implementation for fetch(_:) one step at a time. Note that the code won't compile until we've finished the implementation.

First, we'll want to check the images dictionary to see if we can reuse an existing task or grab the image directly from the dictionary:

public func fetch(_ urlRequest: URLRequest) async throws -> UIImage {

if let status = images[urlRequest] {

switch status {

case .fetched(let image):

return image

case .inProgress(let task):

return try await task.value

}

}

// we'll need to implement a bit more before this code compiles

}The code above shouldn't look too surprising. We can simply check the dictionary like we would normally. Since ImageLoader is an actor, it will ensure that accessing this dictionary is done in a thread safe way (don't forget to refer back to my post on actors if you're not familiar with them yet).

If we find an image, we return it. If we encounter an in-progress task, we await the task's value to obtain the requested image without creating a new (duplicate) task.

The next step is to check whether the image exist on disk to avoid having to go to the network if we don't have to:

public func fetch(_ urlRequest: URLRequest) async throws -> UIImage {

// ... code from the previous snippet

if let image = try self.imageFromFileSystem(for: urlRequest) {

images[urlRequest] = .fetched(image)

return image

}

// we'll need to implement a bit more before this code compiles

}This code calls out to a private method called imageFromFileSystem. I haven't shown you this method yet, I'll show you the implementation soon. First, I want to briefly cover what this code snippet does. It attempts to fetch the requested image from the filesystem. This is done synchronously and when an image is found we store it in the images array so that the next called of fetch(_:) will receive the image from memory rather than the filesystem.

And again, this is all done in a thread safe manner because our ImageLoader is an actor.

As promised, here's what imageFromFileSystem looks like. It's fairly straightforward:

private func imageFromFileSystem(for urlRequest: URLRequest) throws -> UIImage? {

guard let url = fileName(for: urlRequest) else {

assertionFailure("Unable to generate a local path for \(urlRequest)")

return nil

}

let data = try Data(contentsOf: url)

return UIImage(data: data)

}

private func fileName(for urlRequest: URLRequest) -> URL? {

guard let fileName = urlRequest.url?.absoluteString.addingPercentEncoding(withAllowedCharacters: .urlPathAllowed),

let applicationSupport = FileManager.default.urls(for: .applicationSupportDirectory, in: .userDomainMask).first else {

return nil

}

return applicationSupport.appendingPathComponent(fileName)

}The third and last situation we might encounter is one where the image needs to be retrieved from the network. Let's see what this looks like:

public func fetch(_ urlRequest: URLRequest) async throws -> UIImage {

// ... code from the previous snippets

let task: Task<UIImage, Error> = Task {

let (imageData, _) = try await URLSession.shared.data(for: urlRequest)

let image = UIImage(data: imageData)!

try self.persistImage(image, for: urlRequest)

return image

}

images[urlRequest] = .inProgress(task)

let image = try await task.value

images[urlRequest] = .fetched(image)

return image

}

private func persistImage(_ image: UIImage, for urlRequest: URLRequest) throws {

guard let url = fileName(for: urlRequest),

let data = image.jpegData(compressionQuality: 0.8) else {

assertionFailure("Unable to generate a local path for \(urlRequest)")

return

}

try data.write(to: url)

}This last addition to fetch(:) creates a new Task instance to fetch image data from the network. When the data is successfully retrieved, and it's converted to an instance of UIImage. This image is then persisted to disk using the persistImage(:for:) method that I included in this snippet.

After creating the task, I update the images dictionary so it contains the newly created task. This will allow other callers of fetch(_:) to reuse this task. Next, I await the task's value and I update the images dictionary so it contains the fetched image. Lastly, I return the image.

You might be wondering why I need to add the in progress task to the images dictionary before awaiting it.

The reason is that while fetch(:) is suspended to await the networking task's value, other callers to fetch(:) will get time to run. This means that while we're awaiting the task value, someone else might call the fetch(_:) method and read the images dictionary. If the in progress task isn't added to the dictionary at that time, we would kick off a second fetch. By updating the images dictionary first, we make sure that subsequent callers will reuse the in progress task.

At this point, we have a complete image loader done. Pretty sweet, right? I'm always delightfully surprised to see how simple actors make complicated flows that require careful synchronization to correctly handle concurrent access.

Here's what the final implementation for the fetch(_:) method looks like:

public func fetch(_ urlRequest: URLRequest) async throws -> UIImage {

if let status = images[urlRequest] {

switch status {

case .fetched(let image):

return image

case .inProgress(let task):

return try await task.value

}

}

if let image = try self.imageFromFileSystem(for: urlRequest) {

images[urlRequest] = .fetched(image)

return image

}

let task: Task<UIImage, Error> = Task {

let (imageData, _) = try await URLSession.shared.data(for: urlRequest)

let image = UIImage(data: imageData)!

try self.persistImage(image, for: urlRequest)

return image

}

images[urlRequest] = .inProgress(task)

let image = try await task.value

images[urlRequest] = .fetched(image)

return image

}Next up, using it in a SwiftUI view to create our own version of AsyncImage.

Building our custom SwiftUI async image view

The custom SwiftUI view that we'll create in this section is mostly intended as a proof of concept. I've tested it in a few scenarios but not thoroughly enough to say with confidence that this would be a better async image than the built-in AsyncImage. However, I'm pretty sure that this is an implementation that should work fine in many situations.

To provide our custom image view with an instance of the ImageLoader, I'll use SwiftUI's environment. To do this, we'll need to add a custom value to the EnvironmentValues object:

struct ImageLoaderKey: EnvironmentKey {

static let defaultValue = ImageLoader()

}

extension EnvironmentValues {

var imageLoader: ImageLoader {

get { self[ImageLoaderKey.self] }

set { self[ImageLoaderKey.self ] = newValue}

}

}This code adds an instance of ImageLoader to the SwiftUI environment, allowing us to easily access it from within our custom view.

Our SwiftUI view will be initialized with a URL or a URLRequest. To keep things simple, we'll always use a URLRequest internally.

Here's what the SwiftUI view's implementation looks like:

struct RemoteImage: View {

private let source: URLRequest

@State private var image: UIImage?

@Environment(\.imageLoader) private var imageLoader

init(source: URL) {

self.init(source: URLRequest(url: source))

}

init(source: URLRequest) {

self.source = source

}

var body: some View {

Group {

if let image = image {

Image(uiImage: image)

} else {

Rectangle()

.background(Color.red)

}

}

.task {

await loadImage(at: source)

}

}

func loadImage(at source: URLRequest) async {

do {

image = try await imageLoader.fetch(source)

} catch {

print(error)

}

}

}When we're instantiating the view, we provide it with a URL or a URLRequest. When the view is first rendered, image will be nil so we'll just render a placeholder rectangle. I didn't give it any size, that would be up to the user of RemoteImage to do.

The SwiftUI view has a task modifier applied. This modifier allows us to run asynchronous work when the view is first created. In this case, we'll use a task to ask the image loader for an image. When the image is loaded, we update the @State var image which will trigger a redraw of the view.

This SwiftUI view is pretty simple and it doesn't handle things like animations or updating the image later. Some nice additions could be to add the ability to use a placeholder image, or to make the source property non-private and use an onChange modifier to kick off a new task using the Task initializer to load a new image.

I'll leave these features to be implemented by you. The point of this simple view was merely to show you how this custom image loader can be used in a SwiftUI context; not to show you how to build a fantastic fully-featured SwiftUI image view replacement.

In Summary

In this post we covered a lot of ground. I mean, a lot. You saw how you can build an ImageLoader that gracefully handles concurrent calls by making it an actor. You saw how we can keep track of both in progress fetches as well as already fetched images using a dictionary. I showed you a very simple implementation of a file system cache as well. This allows us to cache images in memory, and load from the filesystem if needed. Lastly, you saw how we can implement logic to load our image from the network if needed.

You learned that while an asynchronous function that's defined on an actor is suspended, the actor's state can be read and written by others. This means that we needed to assign our image loading task to our dictionary before awaiting the tasks result so that subsequent callers would reuse our in progress task.

After that, I showed you how you can inject the custom image loader we've built into SwiftUI's environment, and how it can be used to build a very simple custom asynchronous image view.

All in all, you've learned a lot in this post. And the best part is, in my opinion, that while the underlying logic and thought process is quite complex, Swift Concurrency allows us to express this logic in a sensible and readable way which is really awesome.