Death by papercut (why small optimizations matter)

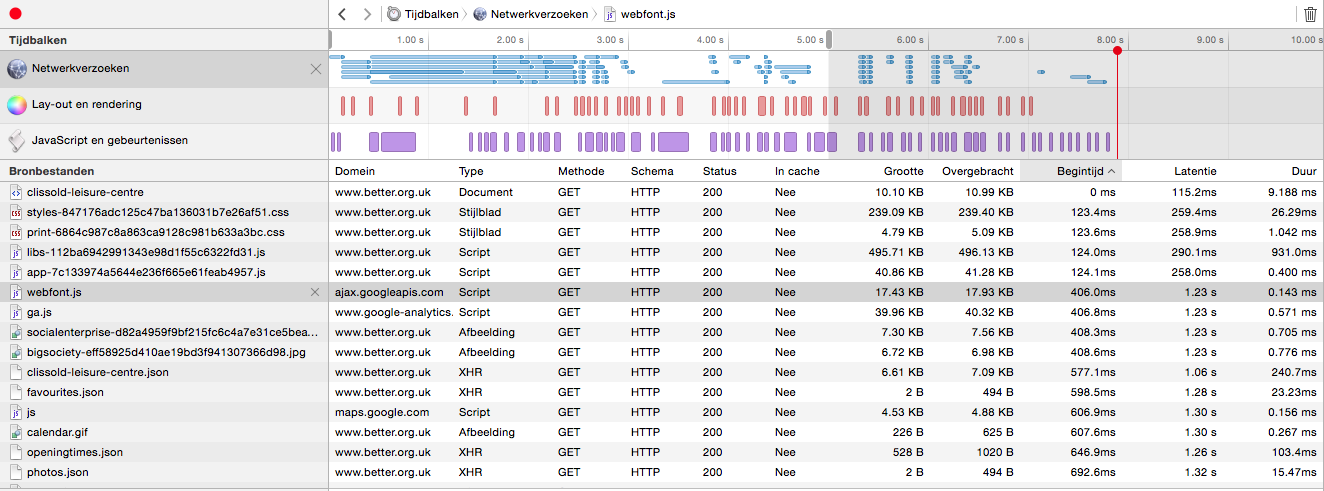

It's not easy to write good code. It's also not easy to optimize code to be as fast as possible. Often times I have found myself refactoring a piece of code multiple times because I could make the code easier to read or perform faster. Sometimes I've achieved both. But when a project would grow larger and larger things would still feel a little slow after a while. For instance, changing something from doing four API calls to six wouldn't matter that much, right? I mean, each call only takes about 10ms and everything is very optimized!

This is death by papercut

In the example I mentioned above, doing two API calls, 10ms each, isn't a very big deal in itself. What is a big deal though, is the fact that we're doing four other calls as well. So that means that we went from 40ms in API calls to 60ms. that's a 50% increase. And then there's also the overhead of possibly extracting the data you want to send to the API from the DOM and also parsing the API's response on the client will take extra time. Slowly all these milliseconds add up. On their own every part of the application is pretty fast, but when put together it becomes slower and slower.

I'm not sure where I heard this first but I think it's a great one. All these not-so-slow things stacking up and then becoming slow is like dying from papercuts. Each cut on it's own isn't a big deal, but if you do enough of them it will become a big deal and eventually you die a slow and painful death. The same is true in web development, and any other development field for that matter.

So if we should avoid dying by a papercut, and papercuts on their own don't really do damage, how should we do that? Every block of code we write will cost us a very tiny bit of speed, that's inevitable. And we can't just stop writing code in order to keep everything fast, that's not an option.

Staying alive

The death by papercut scenario is a difficult one to avoid, but it's also quite simple at the same time. If you take a good hard look at the code you write you can probably identify small bits of code that execute but don't actually do much. Maybe you can optimize that? Or maybe you're doing two API calls straight after each other. One to fetch a list and a second one to fetch the first item on that list. If this is a very common pattern in your application, consider adding the first item in that initial API response. The win won't be huge, but imagine finding just 4 more of these situations. You may have just won about 50ms of loading time by just optimizing the obvious things in your API.

Recently I came across an instance in my own code where I wanted to do a status check for an X amount of items. Most of the items would keep the default status and I used an API to check all statuses. The API would check all of the items and it would return the 'new' status for each item. It was pointed out to me that the amount of data I sent to the API was more than I would strictly need to identify the items. Also, I was told that returning items that won't change is a waste of bandwidth, especially because most items wouldn't have to change their status.

This might sound like 2 very, very small changes were made:

- Send a little less data to the API

- Get a little less data back from the API

As small as these changes may seem, they actually are quite large. First of all, sending half of an already small request is still a 50% cut in data transfer. Also, returning less items isn't just a bandwidth win. It's also a couple less items to loop over in my javascript and a couple less DOM updates. So this case save me a bunch of papercuts that weren't really harming the project directly, but they could harm the project when it grows bigger and bigger and more of these small oversights stay inside of the application, becoming harder and harder to find.

Call it over optimizing or call it good programming

One might argue that what I just described is over optimization, which is considered bad practice because it costs quite some effort and yields only little wins. In this case, because the functionality was still being built it was easy to see one of these small optimizations. And the right time to do a small optimization is, I guess, as soon as you notice the possibility to do that optimization.

I haven't really thought of code in this mindset often, but I really feel like I should. It keeps me on top of my code and I should be able to write more optimized code right from the start. Especially when it comes to data fetching from an API or from a database, I think a very careful approach might be a good thing. Let's not send a request to the server for every little thing. And let's not run to the database for every little thing all the time, that's what caching is for. The sooner you optimize for these small things, the easier it is and the less trouble it will cause you later on.