WWDC Notes: Explore structured concurrency in Swift

Published on: June 8, 2021Structured programming uses a static scope. This makes it very easy to reason about code and its flow. Essentially making it trivial to understand what your code does by reading it from top to bottom.

Asynchronous and concurrent code do not follow this structured way of programming; it can’t be read from top to bottom.

Asynchronous functions don’t return values because the values aren’t ready at the end of the function scope. This means that the function will communicate results back through a closure at a later time.

It also means that we don’t use structured programming for error handling (no throws for example).

We need nesting if we want to use the produced results for another asynchronous operation.

An async function doesn’t take a completion handler and is instead marked with async, and it returns a value.

By using await to call async code we don’t have to nest in order to use results from an async function, and we can throw errors instead of passing them to a completion handler.

This brings us much closer to structured programming.

Tasks are a new feature in Swift and they are new in Swift. A task provides an execution context in which we can write asynchronous code. Each task runs concurrently with other tasks. They will run in parallel when appropriate.

Due to deep integration the compiler can help prevent bugs.

Async let task

An async let task is the easiest kind of task.

When writing let thing = something(), something() is evaluated first and its result is assigned to let thing.

If something() is async, you need it to run first and then assign to let thing. You can do this by marking let thing as async:

async let thing = something()When evaluating this, a child task is created. At the same time, let thing is assigned a placeholder. The parent task continues running until at some point we want to use thing. We need to mark this point with await:

async let thing = something()

// some stuff

makeUseOf(await thing)At this point, the parent context will suspend and await the completion of the child task which will fulfill the placeholder. If the async function can throw, you must prefix with try await instead.

When calling multiple async functions in one scope, you can write this:

func performAsyncJob() async throws -> Output {

let (data, _) = try await fetchData()

let (meta, _) = try await meta()

return Output(data, meta)

}This will first run (and await the output of) fetchData, and meta is run after.

After meta is done, we return Output.

If the two await lines don’t depend on each other, we can run then concurrently by using async let:

func performAsyncJob() async throws -> Output {

async let (data, _) = fetchData()

async let (meta, _) = meta()

return Output(try await data, try await meta)

}This will not suspend the parent task until the await is encountered, and both tasks will be running concurrently.

A parent task can spawn one or more child tasks. A parent task can only complete its work if its child tasks have completed their work. If one of the child tasks throws an error, the parent task should immediately exit. If there are multiple child tasks running, the parent will mark any in-flight tasks as cancelled before exiting. Marking a task as cancelled does not stop the task; it’ll just tell the task that its output is no longer needed; the task must handle its cancellation. If a task has any child tasks when cancelled, its child tasks will be automatically marked as cancelled too.

A parent task will only finish when all of its child tasks are marked as finished,

This guarantee of always finishing tasks (either successfully, through cancellation, or by throwing an error) is fundamental to concurrency in Swift.

Cancellation in Swift tasks is cooperative. The task is not stopped when cancelled. A task must check its own cancellation status at reasonable times, whether it’s actually async or not. This means you should design your tasks with cancellation in mind; especially if they are long-running. You should always aim to stop execution as soon as possible when a task is cancelled.

You can do this with try Task.checkCancellation(). This will check the cancellation status for the current task and throws an error if/when it is. If it’s more appropriate you can also use Task.isCancelled. When your task is cancelled you can throw an error which is what Task.checkCancellation() does. But you can also return an empty result, or a partial result. Make sure you document this explicitly so callers of your function know what to expect.

Group task

In the talk a structure like this is shown:

func fetchSeveralThings(for ids: [String]) async throws -> [String: Output] {

var output = [String: Output]()

for id in ids {

output[id] = try await performAsyncJob()

}

return output

}

func performAsyncJob() async throws -> Output {

async let (data, _) = fetchData()

async let (meta, _) = meta()

return Output(try await data, try await meta)

}For every id, one task with two child tasks is spawned. await performAsyncJob is the parent, and fetchData and meta create the child tasks. In the for loop, we only have one active task at a time since we await performAsyncJob in the loop. This means that Swift can make certain guarantees about our concurrency. It knows exactly how many tasks are active at a time.

We can use a task group to have multiple calls to performAsyncJob active. Tasks that are created in a group cannot escape the scope of their group.

You create a task group through the withThrowingTaskGroup(of: Type.self) function. This function takes a closure that receives a group object. You add new tasks to the group by calling using on the group:

func fetchSeveralThings(for ids: [String]) async throws -> [String: Output] {

var output = [String: Output]()

try await withThrowingTaskGroup(of: Void.self) { group in

for id in ids {

group.async {

output[id] = try await performAsyncJob()

}

}

}

return output

}Child tasks start immediately when they’re added to the group.

By the end of the closure, the group goes out of scope and all added child tasks are awaited.

This means that that there’s one task in fetchSeveralThings. This task has a child task for each id in the list. And each child task has several tasks of its own.

The code above would have a compiler error due to a data race on output. It’s being mutated by several concurrently running tasks. Data races are common in concurrent code. Dictionaries are not concurrency-proof; they should only be mutated one by one.

Task creation takes a @Sendable closure and it cannot capture mutable variables. Sendable closures should only capture value types, actors, or classes that implement synchronization.

The Protect mutable state with Swift actors provides more info.

To fix the problem, child tasks can return a value instead of mutating the dictionary directly:

func fetchSeveralThings(for ids: [String]) async throws -> [String: Output] {

var output = [String: Output]()

try await withThrowingTaskGroup(of: (String, Output).self) { group in

for id in ids {

group.async {

return (id, try await performAsyncJob())

}

}

for try await (id, result) in group {

output[id] = result

}

}

return output

}This for try await loop runs sequentially so the output dictionary is mutated one step at a time.

Async sequences are covered more in the Meet AsyncSequence session.

While task groups are a form of structured concurrency, the task tree rules work slightly differently.

When one of the child tasks in the group fails with an error (and it throws), this will cancel all other child task just like you’d expect since it’s the same as async let. The main difference is that when the group goes out of scope its tasks aren’t cancelled. You can call cancelAll on the group before exiting the closure that’s used to populate the task.

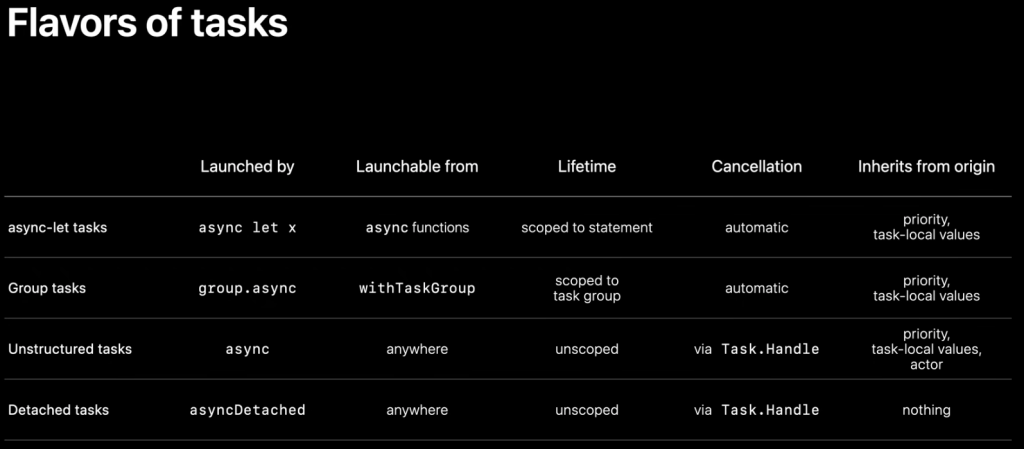

Unstructured tasks

Structured concurrency has a clear hierarchy and defined rules. Sometimes there are situations where you need unstructured concurrency; without a structured context.

For example, you might need to launch something async from a not yet async context. This means you don’t have a task yet. Other times, tasks might live beyond the confines of a single scope. This would be common when implementing delegate methods with concurrency.

Async tasks

Imagine a collection view delegate method where you want to fetch something async for your cell.

This would not work

// shortened

func cellForRowAt() {

let ids = getIds(for: item) // item is passed to cellForRowAt

let content = await getContent(for: ids)

cell.content = content

}So we need to launch an unstructured task

// shortened

func willDisplayCellForItem() {

let ids = getIds(for: item) // item is passed to willDisplayCellForItem

async {

let content = await getContent(for: ids)

cell.content = content

}

}The async function runs code asynchronously on the current actor. To make this the main actor you can annotate a class with @MainActor

@MainActor

class CollectionDelegate {

// code

}- An unstructured task will inherit actor isolation and priority of the origin context

- Lifetime is not confined to a scope

- Can be launched anywhere

- Must be manually cancelled or awaited

SIDENOTE all async work is done in a task. Always.

Cancellations and errors do not automatically propagate when using an unstructured task.

We can put tasks in a dictionary to keep track of them:

@MainActor

class CollectionDelegate {

var tasks = [IndexPath: Task.Handle<Void, Never>]()

func willDisplayCellForItem() {

let ids = getIds(for: item) // item is passed to willDisplayCellForItem

tasks[item] = async {

defer { tasks[item] = nil }

let content = await getContent(for: ids)

cell.content = content

}

}

}Storing the task allows you to cancel it. Should be removed if the task finished. Defer can do this. This way we don’t cancel anything.

Because we run on the main actor (async inherits the actor), we know that we don’t have a data race on tasks. Only one operation will mutate (or read) it at a time.

We can use tasks[item]?.cancel() in didEndDisplay to cancel the task manually.

Detached tasks

Sometimes you want to not inherit any actor information and run a task completely on its own. This can be done with a detached task. They work the same as async tasks but they don’t run in the same context as they’re crated in. You can pass parameters for priority.

Imagine caching the result of getContent in the code. This can be detached from the main actor.

@MainActor

class CollectionDelegate {

var tasks = [IndexPath: Task.Handle<Void, Never>]()

func willDisplayCellForItem() {

let ids = getIds(for: item) // item is passed to willDisplayCellForItem

tasks[item] = async {

defer { tasks[item] = nil }

let content = await getContent(for: ids)

asyncDetached(priority: .background) {

writeToCache(content)

}

cell.content = content

}

}

}This task will run on its own actor and takes a low priority since it’s not super important to do it as soon as possible.

In a detached task you can create a task group. This would allow you to run a bunch of async work concurrently, and to cancel this work easily by cancelling the detached task since the detached task would be a parent task for all child tasks.

asyncDetached(priority: .background) {

withTaskGroup(of: Void.self) { group in

group.async { writeToCache(content) }

group.async { ... }

group.async { ... }

}

}Since the detached task is a background task, the priority also applies to all of its child tasks.

Tasks are just part of Swift concurrency. They integrate with the rest of this large feature.

Tasks integrate with the OS and have low overhead. The behind the scene sessions provides more info.